How sustainable are Ghana’s mining reforms to dissuade informal miners from returning?

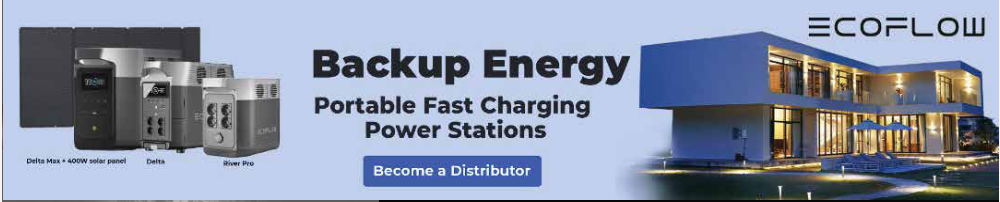

ASM, a practice in Ghana for over a century, contributed to 40% of total gold production in 2016 and generated two billion US dollars. In 2018, it generated 2.1 million ounces of gold, employing 60% of Ghana’s mining workforce. However, it also causes water pollution, land degradation, and hazardous element discharge (see Fig. 1).

The Ghanaian government has been working to formalize mining operations through six main channels to improve environmental performance, address safety concerns, and increase the sector’s benefits. However, these reforms have come at a cost, including water pollution, land degradation, destruction of valuable agricultural fields, and the discharge of hazardous elements such as mercury into soils and water supplies.

Fig. 1: Environmental pollution associated with artisanal mining in Prestea. A: Mercury pollution. B: Massive erosion on the land caused artisanal miners. C: Massive sedimentation of a river caused by artisanal miners. D: Polluted ‘Asesre’ river. Source: Mensah and Tuokuu (2023).

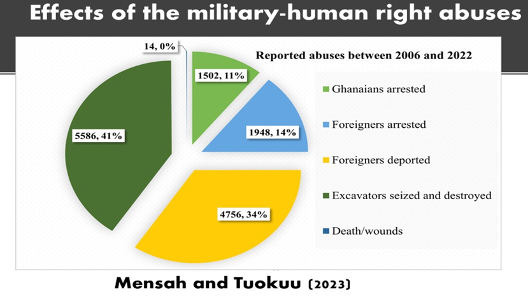

To address these issues, the government has implemented reforms to clean up the operations of artisanal and small-scale mining. These reforms include policy interventions, a complete ban on their operations, military strategy, national dialogue, alternative livelihood programs, and community mining. Security troops have been stationed in illegal mining areas to dissuade miners who work there without a government permit, which often results in injuries, cruelty, confiscation or destruction of expensive mining equipment. This technique has been criticized by scholars for its human rights abuses and casualties (see Fig. 2)

Fig. 2: Reported human right abuses caused by the military intervention against artisanal miners in Ghana. Source: Mensah and Tuokuu (2023).

In 2017, the government formed the Inter-Ministerial Committee on Illegal Mining (IMCIM) and a task force, which was made up of political party supporters and members. Their operations and responsibilities were equally informal and non-scientific. However, all seven of the IMCIM’s tasks have already been fulfilled by appropriate oversight agencies such as the water resources commission, forestry commission, minerals commission, environmental protection agency, and others. Members of the IMCIM were caught in the act of corruption when their boss and secretary were caught on camera accepting bribes to allow the illegality of informal mining to continue.

The informal mining sector in Ghana is complicated, and a holistic approach incorporating miners, local communities, and a bottom-up approach is required to address it. By bringing in technocrats from different industries with research experience in the topic and removing politics from the discussion, a bottom-up approach is required to address the challenges faced by the informal mining sector in Ghana.

Agriculture and mining may be the only two significant competing occupations in Africa’s rural economies. In rural Africa, the majority of farmers and miners are smallholders and artisanal miners, respectively. In terms of revenue creation and poverty alleviation in peri-urban and rural economies, the latter outcompetes and has a competitive edge over the former. Over a million people are employed in Ghana’s artisanal and small-scale mining sector alone, with an estimated double as many people working in the informal or artisanal sector.

Large-scale mines exist to increase national income and foreign exchange earnings for the national economy, but the beneficial economic impacts on the local areas where they operate are minimal. Mining operations in Tarkwa displaced 14 agricultural settlements totalling 30,000 people between 1990 and 1998, while Newmont’s first phase of the Ahafo South Project displaced 9,500 rural farmers. Additionally, the company’s cyanide spill in 2009 killed a large number of fish, harmed water quality, and impacted aquatic biodiversity in riparian communities.

In conclusion, small-scale mining operations have been found to reduce poverty by providing fiscal revenues for investment in healthcare and education, acting as a catalyst for economic growth in host mining communities, providing direct employment to indigenous peoples, initiating private investments in public goods, and initiating corporate social responsibilities. Large-scale mining, on the other hand, has been linked to poverty exacerbation by causing economic underperformance, exacerbation of inequality, volatility in employment, economic enclaves, rent seeking and corruption, environmental and social consequences.

Artisanal Small-Scale Mining (ASM) may represent the future of Ghana’s mining industry, as it has never been regarded as a critical component of a national poverty-reduction plan. Prospective licensees must undergo a series of bureaucratic formalities, make multiple pricey fees, and in some cases travel huge distances to consult officials. With relatively little effort, simplifying the licensing regime for operators and cutting permit costs could support the formalization of ASM while also securing a new, desperately needed source of taxation for itself.

Ofosu-Mensah (2017) wrote a 25-page book, “Historical and Modern Artisanal Small-Scale Mining in Akyem Abuakwa, Ghana.” The research focuses on the micro components of the resource-curse theory, which claims that “an abundance of natural resources in underdeveloped nations is associated with unfavourable developmental consequences.” He examines the issue through the lens of Akyem Abuakwa, Ghana’s largest mining village.

To address the issue of illegal mining, it is necessary to examine the topic of why miners are unlawful in the first place. Small-scale mining’s prosperity and safety are dependent on the industry’s organization and regulation. Some studies have suggested that releasing land and regularizing operators will permit better planned and environmentally more benign activities.

The way forward is to establish long-term solutions to regulate the sector, examining the effectiveness of institutional arrangements in charge of this sector, the extent to which various institutional systems collaborate and coordinate, and the relationship between institutions in charge and research institutions. Regular monitoring and auditing to ensure that standards are met and protocols are followed are essential.

It is important to recognize that the illegalities of the ASM sector are not a threat, but rather that corporations will create for profit without regard for environmental or social considerations when there is a regulatory vacuum. Prohibiting and criminalizing informal mining is not a viable alternative. Instead, we can effectively regularize the sector, acknowledge it, accept it as our own, organize it, sanitize it, capitalize on its potential, and use it as a mainstream poverty alleviation instrument in mining towns.

The ASM sector is complex, and it is unfortunate that many people do not comprehend it. The way forward in the future will be to reduce the environmental and human safety implications while also leveraging the sector’s potential for poverty alleviation in rural economies. These can result from deliberate attempts to formalize the sector through strong regulations and strict implementation of current regulatory frameworks. Concerted efforts may be taken to make the artisanal and small-scale mining sectors function for the betterment of our mining communities.

By Albert Kobina Mensah, Ph.D.

Reference

Ofosu-Mensah, E. A. (2017). Historical and modern artisanal small-scale mining in Akyem Abuakwa, Ghana. Africa Today, 64(2), 69-91.

This article is based on the full paper:

Mensah AK and Tuokuu FXD (2023), Polluting our rivers in search of gold: how sustainable are reforms to stop informal miners from returning to mining sites in Ghana? Front. Environ. Sci. 11:1154091. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2023.1154091